When Demeter and Persephone tapped me on the shoulder late in 2019, I made no immediate association between them and Frances, Countess Purbeck, 17th century protagonist of Nights of the Road, or her mother, Lady Elizabeth Hatton. My only impetus was to search out their original myth, which I found in a translation of its first known written version, Homer’s 3,000 year old lyrical Hymn to Demeter.

I didn’t know why I should spend any time with this particular myth, but my intuition, however fleeting and fuzzy, alerts me when characters and places from the past want me to read their story. Whisperings of 400-year old exhumed bones of Eliza Hatton in a London cemetery being cleared for property development had once stirred me into researching her story and that of her daughter, Frances. I was rewarded, in so many ways not anticipated, by following their trail and bringing it to twenty-first century life.

Following an intuition from its first easy-to-miss signals to a fully emergent story is not the way of all writers, yet many an author of historical fact and fiction testifies that such messages, seemingly carried on the wind, source and feed their creative process. Perhaps people from the past whose souls and stories are not yet at peace find fitting wordsmiths to do their unfinished work, when the moment is ripe…

Just as with Elizabeth and Frances, so with Demeter and Persephone, I quickly became immersed in research. And the more I found, the more eager I became to learn more.

A natural disposition to see evolutionary patterns weaving future-past into present had me tracking how the myth might have evolved with repeated telling. I soon realised that this is no dusty, ancient story, but one that invites personal and public contemplation and even concerted action today

Homer’s Legacy

Homer presented Demeter and Persephone nearly 3,000 years ago as a myth rooted in nature, that both reflected the physical landscape and spiritual belief system in which people lived, and also guided them on how they might survive and flourish in life and prepare for a healthy death.

His descriptive and lyrical prose described a world of gods and goddesses where power is equally if differently distributed between the sexes. Patriarchy and matriarchy each have their place. In Homer, the ruling masculine has the power to decide where and whom its daughters (and sons) shall marry, yet the feminine has the ultimate say in whether a marriage is fertile and fruitful.

Diplomacy is active, with both masculine and feminine messengers used to grease any squeaky wheels. Relations within and between the realms of sky, earth and underworld are for the most part amicable, perhaps reflecting a prevailing desire among the ancient Greeks for peace, balance and amity between regions and city states? Interactions between humans and gods in daily life – and their mutual reliance one on the other – is also spelled out.

The overall tone in the myth is benign. Demeter may rage and grieve when her child is lost and even take it out on mortal and god by withdrawing her favour. Yet she does not want revenge on Hades for abducting Persephone; she simply wants her daughter back.

Once that’s been achieved, she’s ready to smile and consort again with her sibling gods and goddesses, as well as share with humans her secrets, from how to plough and sow a field to sacred rites that can ensure spiritual blessings in life and beyond. Zeus looks for a solution fair to all and in alignment with universal law, in making his final ruling, albeit in a situation that he as an absent father has set in motion.

Time and Times Transform Tales

I found it striking to observe how a relatively light patriarchal overlay intensified and progressively distorted Homer’s version in the retelling of the myth through succeeding millennia. It was particularly evident in the naming, blaming and diverting of responsibility from male to female gods.

Hundreds of years after Homer, the Latin poets were hard at work, transforming key aspects of the plot, its characters and their inter-relationships! In the expansionary days of the Roman Empire, poets like Ovid and Virgil were writing to both entertain and please their emperors’ ambitions, as much as to satisfy their own poetic muse.

By the time of ancient Rome, the gods and goddesses had become aloof and distant deities who were to be prayed to for the maintenance of universal law and order. They no longer interacted with humans. Might was now right. Power and territorial conquest had become the goal of successive emperors. This was the day of the Roman legion and centurion. War became a tightly drilled profession and – as in all wars – women and children typically got ‘the short end’ of any spiritual and physical sticks in myth and in life!

Ovid shifted responsibility for the abduction of Persephone (now Proserpina) away from Zeus and laid it instead at the door of a power-hungry goddess of desire, Aphrodite (Venus), trying to extend her territorial reach into the Underworld. In his Metamorphoses, she opportunistically uses an earthquake to have her son Eros (Cupido) shoot an arrow into Hades’ (Pluto’s) heart. It is this that enflames Hades’ and impels him to carry Persephone off.

The Metamorphoses of Ovid, pl. 46 Second edition. Italy, published 1606 LACMA.

Scorn and criticism frequently erased Homer’s judgment-free descriptors by the times of Roman texts. Ovid subtly demeaned Persephone and her companions for picking flowers – “The worthless booty entices their girlish minds.” Virgil’s Sybil in The Aeneid thought little of a daughter of Zeus who continues willing to “warm the bed of her uncle in a very un-Roman sort of marriage” (See Persephone in the Aeneid.pdf by Lee Fratantuono)

By the end of the Aeneid, Virgil had cast doubt even on the very existence of Persephone and the Elysium fields of the Underworld over which she ruled.

Rivalry and dissension between the goddesses flourished in Roman versions of Demeter and her daughter. Lucan in his Pharsalia suggested that, far from being pleased to return to the upper world each springtime, to assure the rhythm of the seasons and the fertility of harvest as described by Homer, Persephone actively hated both Heaven and her mother. The relationship air darkened further, when Ovid introduced whistleblower Ascalaphus, who tells of Persephone eating the pomegranate seeds, apparently “from spite” rather than the simple diligence of a gardener in charge of the orchard and its fruit.

In the Aeneid, Heaven and the Underworld are at odds when Juno, goddess of marriage – and Virgil’s pre-eminent goddess – usurps Persephone’s ruling role in the realm of the dead by sending Iris to cut a lock from Dido’s hair and hasten her soul’s descent to the Underworld.

Seventeenth Century Perspectives

Disparagement of the feminine, liberally seeded in Roman times, received moral fuel throughout the Christian and mediaeval period and on into the Renaissance. Ovid was a frequent source for Shakespeare’s 16th and 17th century plays.

In his The Tempest, Aphrodite’s (Venus’) lust to extend her power into the Underworld is the origin of Persephone’s woes rather than paternal disregard for the wishes of mother and daughter. Shakespeare reinforces patriarchal divide-and-rule, by pitting feminine explicitly against feminine: Demeter (Ceres) is not even willing to be in the same place as Venus!

Tell me, heavenly bow (Iris),

If Venus (Aphrodite) or her son, as thou dost know, .

Do now attend the queen? Since they did plot

The means that dusky Dis (Hades) my daughter got,

Her and her blind boy’s scandal’d company

I have forsworn.

And Ceres will only stay to bless the engaged couple, Ferdinand and Miranda, once she has been assured by an uncharacteristically sharp-tongued rainbow goddess that:

Here thought they to have done

Some wanton charm upon this man and maid,

Whose vows are, that no bed-right shall be paid

Till Hymen’s torch be lighted: but in vain;

Mars’s hot minion is returned again;

Her waspish-headed son has broke his arrows,

Swears he will shoot no more but play with sparrows

And be a boy right out.

Hecate’s reputation fared no better than that of Aphrodite, at the Bard’s hand.

In Homer, the goddess Hecate, she “of the splendid headband”, had appeared in a supportive, guiding role to Demeter and later to Persephone. She puts her awareness and wisdom selflessly at the service of both and, after Zeus final ruling is declared and implemented, she constantly accompanies and acts as substitute for Persephone, to enable the Queen of the Underworld’s return to upper earth each spring.

This benign personification of Hecate bears no relation to how she appeared on the 17th century Shakespearean stage, at a time when women were being burned at the stake for serving society with their wise-woman healing skills. In Shakespeare’s Macbeth, Hecate is the angry and fearsome goddess of witches: “the close contriver of all harms” who declares: “This night I’ll spend unto a dismal and a fatal end.”

Shakespeare influenced customs and attitudes of the day with his prolific works, but he was also serving his monarch’s wishes and whims, while reflecting back to society its mores. Macbeth was set in the King’s homeland, dealt with the witchcraft that obsessed James I, and was also intentionally timed to be short, to suit His Majesty’s wandering attention!

This was a time when responsibility for Persephone’s woes – as for those of any young 17th century girl abducted and obliged to marry against her will – were less likely to be attributed to casual abuse of physical strength and power of position than to feminine whiles. Temptresses, young and old, were considered capable of casting dark magic spells and stirring the desires of otherwise blame-free mortal men and gods.

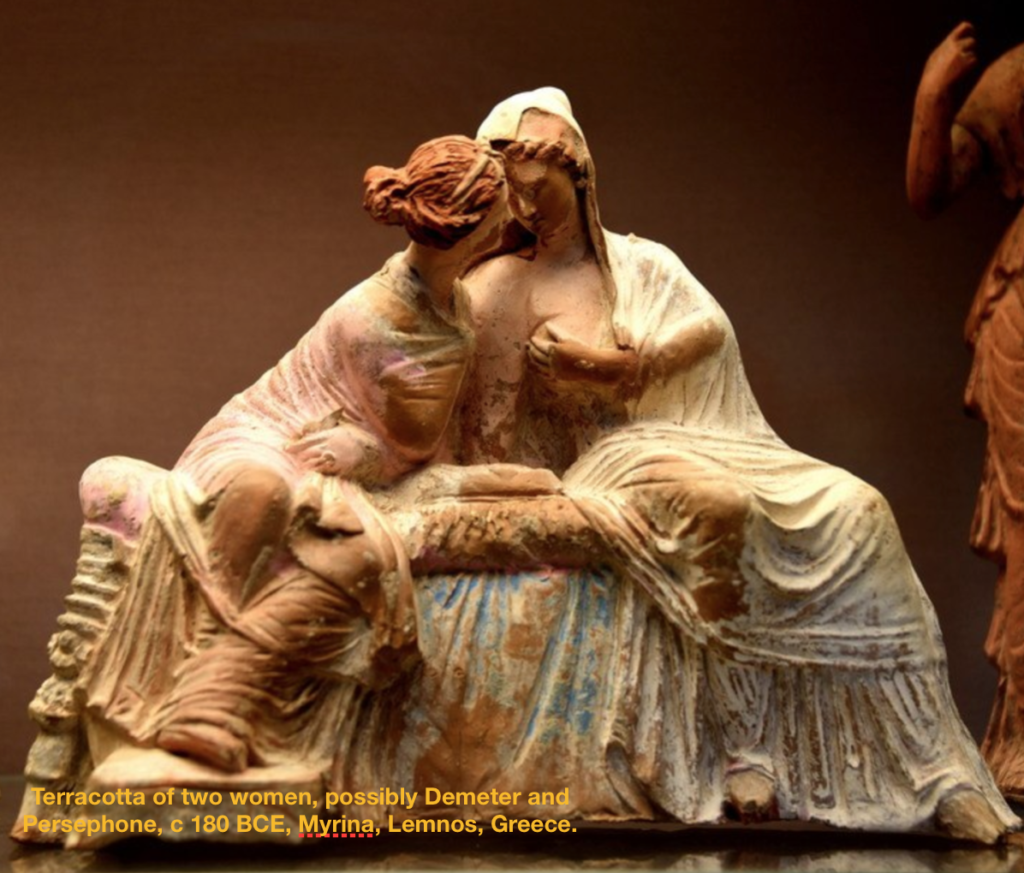

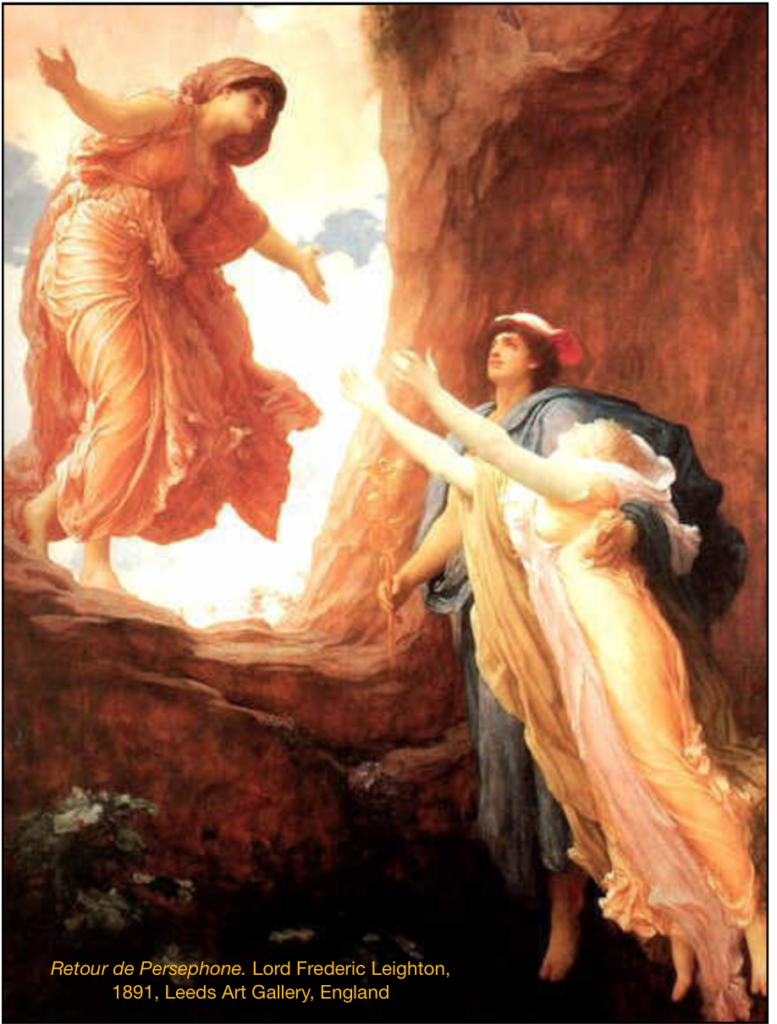

Just as wordsmith adapted their texts according to the wishes of their masters and their public, artists also transformed the visual form of the Demeter and Persephoe myth over the centuries, both influencing and reflecting the mores and attitudes of the age in which they lived.

Compare the naked and voluptuous vigour of Bernini’s famous Sculpture of Hades and Persephone above with the fully clad and chaste representation of Persephone and her mother in Victorian artist Lord Frederick Leighton’s canvas, nearly three hundred years later:

Still to Come…

In my next post, I’ll be exploring the evolution and transformation of the Demeter and Persephone myth over the last several hundred years. The arrival of the Jungians has brought a whole new dimension of study through Archetypal Psychology. This feeds a focus on the symbolism of both major and minor characters within the myth.

Over time, this influence has encouraged a growing wave of feminist political revision of history and myth, which continues into this day and can sit both comfortably and uneasily alongside the use of myths to entertain at the box office with blockbusters like Star Wars.

I’ll be looking at how the Hades and Persephone underpinning of Kylo-Ren’s relationship with Rey recently provoked a storm of public debate on agency, co-dependency and the place of redemption in The Rise of Skywalker. I’ll also be considering how events in daily life around the world show that this ancient tale has never been more alive and potent in society, and inviting our serious attention.

For now however, the beginning of the seventeenth century feels an appropriate and relevant place to pause.

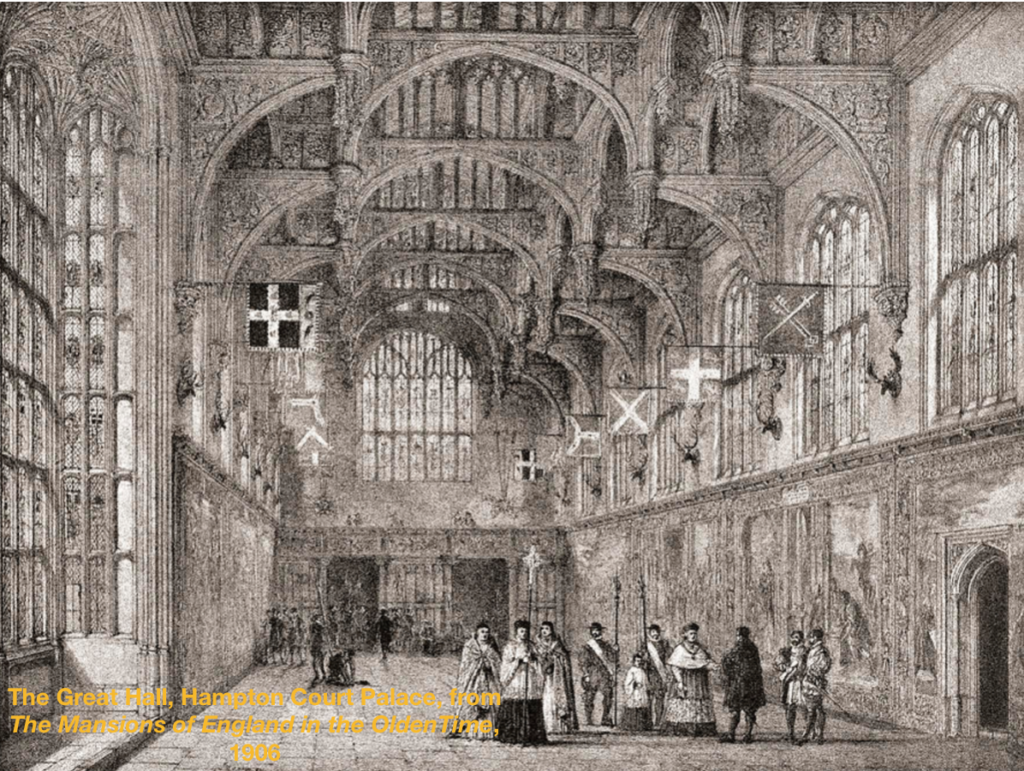

Macbeth and The Tempest were both conceived and performed first at the Court of England’s new king, James the First. Macbeth was first performed in the Great Hall at Hampton Court where, little more than a decade later, the girl Frances Coke would endure the nightmare feast that accompanied her wedding to Sir John Villiers, after being abducted and forced into marriage against her will as described in Nights of the Road.

Ironically, it was only a few days ago, when creating a page on my website – to describe a weekend Gene Keys Demeter and Persephone workshop I’ll co-host with friends in late May in Mount Shasta – that a thunderbolt (from Zeus?) shook me violently awake. I then made the latest of a number of unanticipated connections that this eternal myth has been revealing, since it tapped me on the shoulder late last year.

The experience of Lady Elizabeth Hatton and her daughter Frances, Countess of Purbeck was a seventeenth century real life version of Demeter and Persephone… !

So a myth that has tapped me on the shoulder and invited me to revision and serve it in a different form than a novel is also the archetypal structure underpinning a novel I first began to write twenty years ago? Hmm… Why did I not see this connection between my novel and the myth sooner?

Perhaps I had not yet spent enough time with my own inner Zeus to be able to see clearly my own personal underworld wood for the trees! Whatever the reason, intuition tells me today that this story has more treasures to yield, within and outside me, before a group of us gather – in a mountain setting as magical, mysterious and redolent of its own mythic past as Mount Olympus – to sow and perhaps reap some personal and collective harvests in May…