My search for crumbs from Viscount Purbeck’s life story table led me back this week to 17th century medicine, and thence on to poetry. It also sent me down a wormhole into the world of apothecaries, distillers and other London guilds. All of this came out of remembering a letter reporting that in 1632 King Charles consigned John Villiers to the physical care of one Doctor Thomas Cademan, who prescribed for him no tobacco nor wine and no visitors, except those who had accompanied him out of the country.

Born in Norfolk about 1590 and educated at Trinity College, Cambridge, Cademan was Catholic and chose to study medicine in the renowned university of Padua.

He received thereby a far broader and more effective education than many Protestant compatriots but, once home again, his religion delayed him being accepted in the College of Physicians. Thomas passed his College exams in 1623 but only received his license in1630. His faith did not prevent him acquiring wealthy and influential patients. He became physician to Queen Henrietta Maria, to members of the royal household like Sir John Gill, to nobility such as the Duke of Bedford, and to Sir William Davenant, poet laureate and playwright.

Davenant paid his doctor’s bill in 1624 with an adulatory poem, in which he praised Cademan’s knowledge and lack of pedantry as well as his ‘ready heart’. Well he might, since Thomas had saved Davenant not only from the worst ravages of syphilis, but also arrested the effects of earlier disfiguring and nearly fatal treatment with ‘that no God, but Devil Mercurie.’

Davenant catalogued in verse the good that Cademan had done him, while depicting in lurid detail the fate of unfortunates denied the great doctor’s care, in particular wounded military men. The bigotry of his views on ‘heathen adversaries’, Muslims and Jews – including their apparent responsibility for the medical condition about which Davenant considered himself blameless – is breathtaking, until one meets the consolatory poem he would send the Duchess of Buckingham four years later, assuring her that the nation shared her grief, when her husband was assassinated. It is one thing not to speak ill of the dead, but Nights of the Road readers will observe how far Davenant’s picture is from the memory of the infamous and almost universally detested Duke:

‘For now is gone the Pilot of the State

The Courts bright Star, the Clergies Advocate,

The Poets highest Theame, the Lovers flame,

And Souldiers Glory, mighty Buckingham!’

Bigot and man of doubtful judgement as Davenant was, viewed with a 21st century lens, his views on ‘heathens’ were commonplace for the times (and echo strongly still in certain quarters in our world today). He did at least forebear from attacking that usual third target for 17th century castigation, the Catholics, one assumes out of respect for his physician.

Withal, Sir William’s poem to Cademan has a quirkish humor. It lists his many debts to the doctor, while deliberately deferring any expected expression of thanks, and finishes with a playful twist: wishing every spring will bring ‘Ripe Plenty of Diseases’ to the wealthy and ‘Health to the Poor’ so that Cademan will not feel obliged to treat more patients like Davenant out of charity.

We need not weep for Thomas that Davenant’s hand stayed in his pocket, even if the doctor did subsequently appear in arrearage lists of early 1640’s Westminster rate books.

This may have been from oversight rather than impecunity, since receipts for his payments are recorded elsewhere and Cademan long enjoyed royal patronage not only in terms of patients, but also in lucrative distilling monopolies from the King. He would also soon acquire a rich wife, about which more below. Let’s first stay awhile with his early career.

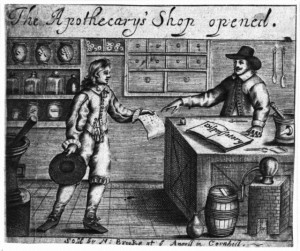

Thomas Cademan was influential in helping the Society of Apothecaries obtain its Charter on 6th December 1617. It had not been hard to interest the King in signing such a charter, for James took the health of his subjects to heart and reform of apothecary practices in England was long overdue. Rumors had circulated that his own son’s death in 1612 resulted not from typhoid fever but from poison, whether intentional or through administration of bad medicine. Such rumors were fanned by no less a personage than Sir Edward Coke, already known to readers of Nights of the Road. As a man of law, Coke usually refrained from idle gossip, but he was reported to have declared darkly: “God knows what became of that sweet babe Prince Henry but I know somewhat…”

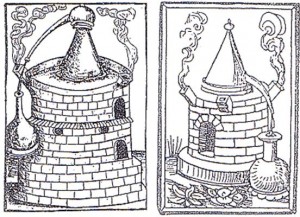

Apothecaries needed great skill for they were not just drug retailers. They had to recognize plants, and learn their properties and qualities, as well as how to extract their essences. They weighed and mixed compounds and prepared medicines with sophisticated techniques of fermentation, filtration and distillation. Apprentices served seven years and passed an oral exam to become a freeman of the company. Incompetent apprentices could be dismissed. Members of the guild had the right to enter any shop within seven miles of London to assess if medicines on sale were good. They had the power to fine and remove licenses.

Given their early support from doctors, one might have expected the Society of Apothecaries to keep Thomas Cademan and colleagues close. Such powerfully placed individuals helped them remain separate from a parent liveried company, the Grocers, who did not appreciate ‘having a limb cut off’ and their activities curtailed. Continuing support of the Royal doctors, and through them the King, was vital to maintain Apothecary independence, while the Grocers played out a vigorous but unsuccessful rearguard action.

Given their early support from doctors, one might have expected the Society of Apothecaries to keep Thomas Cademan and colleagues close. Such powerfully placed individuals helped them remain separate from a parent liveried company, the Grocers, who did not appreciate ‘having a limb cut off’ and their activities curtailed. Continuing support of the Royal doctors, and through them the King, was vital to maintain Apothecary independence, while the Grocers played out a vigorous but unsuccessful rearguard action.

Unfortunately, relations cooled. Far from showing gratitude and deference, Apothecaries became resentful of the College of Physicians, accusing them of unreasonable interference. Doctors meanwhile expected apothecaries to confine themselves to producing medicaments requested and approved by physicians rather than setting themselves up as alternative healers. They demanded a final say in which apprentices received freeman status. They also entered apothecary shops to search and prosecute for ‘bad drugs.’

Animosity spilled into open warfare in the late 1630’s when Cademan and colleagues persuaded Charles I to grant a charter for the Company of Distillers, of which Cademan was the first president, thereby consolidating his own distilling monopolies.

The Apothecaries now reversed roles by attempting, as unsuccessfully as the Grocers before them, to destroy the new guild that they felt threatened their business.

Squabbles and power play between and among King, royal doctors, Parliament and the many liveried companies of London suggest that pre-Civil War fault lines were much more fragmented and complex than represented in simplistic accounts of early 17th century divisions between Court and City.

They also read uncannily like struggles between modern day pharmaceuticals, mainstream and alternative medicine, and government regulatory bodies around the world. During clashes, the rhetoric of all sides and time periods is invariably couched and presented in terms of the public and patient wellbeing, yet one never need look far in either era to spot the money trail and the role of personal vested interests.

In 17th century England, the King no doubt wanted to protect his subjects from quacks selling useless or dangerous medicines, but his Exchequer also relied heavily on the portion of monopolies money that went to the Crown. He was quick to hold out his cap to the liveried companies for special loans, as in the case of 10,000li he demanded in 1620 for aid and relief of the Palatinate.

Initially, the City allotted the newly chartered Apothecaries just 20li of this sum. The Apothecaries harrumphed mightily at the amount, for they had been granted a monopoly with no endowment. They had just 50li and a few silver spoons in their coffers, and were looking to set themselves up in a hall.

But they paid up with whatever grace they could muster and in truth were getting off lightly for, in today’s purchasing power, their share was only about $5,500 of a city loan of just under $3 million.

Enter the Grocers, who screamed that the Apothecaries should pay more. An appeal to the Court of Aldermen, with which the powerful Grocers had leverage, brought a revised joint assessment of 500li. The Grocers promptly announced their portion was 300li, leaving the Apothecaries to find 200li. This tenfold increase in what had already felt onerous came as a shock to the Apothecaries, but their appeal to the House of Lords fell on deaf ears, so their own wealthier officers were obliged to dig deep into personal pockets to cover the equivalent of $55,000 to keep the young guild afloat. That they did so speaks to their staunch refusal to be swallowed again by the Grocers and to the potential rewards of preserving separate chartered status. For, if apothecaries were sometimes styled as the poor man’s doctor, many of them became very rich and influential. Their important role in offering facilities for scientific experiments also gave them a favored position with members of the newly formed Royal Society.

One such prominent and wealthy apothecary was Thomas Crosse, who died in 1641. In a century when a woman could not legally own property, she could not be made free of the Company of Apothecaries and so could not practice, with one type of exception. In 1642, Anne Crosse became one of three known London widows allowed by the Company of Apothecaries to run their family shops after their husbands’ deaths. www.chemheritage.org/discover/media/magazine/articles/27-3-womens-business.aspx

In spite of the years spent working alongside her husband, Anne was not deemed experienced enough at his death to train an apprentice alone. In 1642 the Company declared her apprentice, Thomas Clarges, unlawful and found her a journeyman apothecary to help her run the business and train her apprentice. It was 1646 before Clarges (brother to a seamstress who would become Duchess of Albemarle) would be admitted to the Company of Apothecaries, by which time Anne had married a friend of her husband. His name? Doctor Thomas Cademan!

The two Thomases had known each other as apothecary and doctor, while providing medical support to the Royal family and the Royalist army. By his marriage, Cademan gained a wealthy widow, an apothecary shop and control of all future medical supplies; Anne gained a chartered Distiller and husband who continued to practice medicine and lecture at the College of Physicians while the Civil War rumbled on around them and business had never been more brisk.

The Society of Apothecaries, the College of Physicians and the Company of Distillers thus at last settled their differences and knew active cooperation in at least one 17th century household!

Thomas Cademan lived almost another decade, before dying at the respectable age of sixty one in 1651. But Dame Anne was not yet done. She married a third time.

Her new husband? One William Davenant, former poet laureate and playwright. Thanks to Anne, he could now get his medicines free and presumably could also afford to pay his doctors’ bills. Whether or not he did so, I have yet to discover…